TEHRAN OF TREES

TEHRAN OF TREES proposes to rethink trees as historical characters, knowledgeable and dreaming beings rooting their memories in us and in Tehran. A multiplicity of human and non-human perceptions coexist in the city as its lifeworld keeps redefining itself. Within this project, artists and researchers Goda Palekaitė and Sina Seifee embark on a fathomless journey through the veins of trees and the rigmaroles of mycelia. TEHRAN OF TREES is made of long-distance calls, looped sounds, biological poetry, animated organisms, ancient travelogs, invisible camera eyes, memories, and imagination.

Acknowledgment: Christian Hansen (sound), Parnian Toosi (botanical advisor), Ehsan Barati (photography), Arthur Debski (proofreading), and the kind support of Foad Farahani, Elmira Mirmiran, Maryam Farshad, Azadeh Dalir, and Sana Ghobbeh.

Project Odyssey

In the name of times when narratives related to plants and other non-humans were told from the perspective of the one who stands erect and walks on two feet, we tell this story. Descriptions of the heavenly garden, which have been central in our literature and cultural imaginary, are filled with springs, wells, streams, trees, flowers and birds. When we gathered in The Conference of the Birds, disguised as humans and with Farid ud-Din Attar, the bird-watcher, as our guide, we realized that these entities usually represent our virtues and qualities. Birds were sources of wisdom for those who were not bird-like. While leaning against an ancient tree, which was as old as Attar, we thought: what if we tried to rethink trees as historical characters in a story, weaving them together with a multiplicity of local human and non-human perceptions coexisting in the city that was made of a grey substance and whose name we did not know yet.

In the name of times when narratives related to plants and other non-humans were told from the perspective of the one who stands erect and walks on two feet, we tell this story. Descriptions of the heavenly garden, which have been central in our literature and cultural imaginary, are filled with springs, wells, streams, trees, flowers and birds. When we gathered in The Conference of the Birds, disguised as humans and with Farid ud-Din Attar, the bird-watcher, as our guide, we realized that these entities usually represent our virtues and qualities. Birds were sources of wisdom for those who were not bird-like. While leaning against an ancient tree, which was as old as Attar, we thought: what if we tried to rethink trees as historical characters in a story, weaving them together with a multiplicity of local human and non-human perceptions coexisting in the city that was made of a grey substance and whose name we did not know yet.

Most of us were writers, visual artists, artistic researchers, anthropologists, performers, storytellers and computer programmers, living and working across countries and continents. With the heightened attention to both noise and knowing, we were tempted to explore the agency of dreams and imagination, and to cultivate an interest in narratives and contexts of contradictory geographies and temporalities and the ideas and ideologies that they contain. We learned that the mysterious grey city was named Tehran and, once the fruits of the tree we had been leaning on were ripe, we proposed to conduct research combining artistic, historical, anthropological and biological perspectives. We were eager to consider ancient and recent characters as trees, as documents, as narratives, and to position them in relation to the biological poetry. We thought of a tree as a remembering person – a tree as a living archive.

We then asked ourselves, how and for whom do we organize remembrance? Persian texts are impossible. Their radical poetic force put us in a position of obligation, in a difficult space of translation, and reminded us of the importance of transforming what is transmitted. Heritage, therefore, can be understood as that which one starts from. Inheriting, as our fairy godmother Vinciane Despret suggests, is an act that demands transformation by its very nature – to honour the problem that is given to us from the past.

However, we were of mixed inheritance. Some were born with 12th century Iranian poetry and a grey map of Tehran’s streets in their veins, and others were born in the dystopia of the USSR. Some had travelled up north to Alemannia and the Low Lands, places where one could live as an artist in order to finally learn how to be an Iranian. Meanwhile, some others had moved south from the blocks of concrete to find out that the world was more colourful than post-soviet capitalism, and on the way passed by Judea, while searching for the legal implications of dreams. This turned out to be a problem for the trees in Tehran. Their roots were entangled in an antagonistic, hostile manner with those in Judea. After a course of negotiations on the international level, our plans to travel to the lands of Tehran entered a loop of uncertainty.

However, we were of mixed inheritance. Some were born with 12th century Iranian poetry and a grey map of Tehran’s streets in their veins, and others were born in the dystopia of the USSR. Some had travelled up north to Alemannia and the Low Lands, places where one could live as an artist in order to finally learn how to be an Iranian. Meanwhile, some others had moved south from the blocks of concrete to find out that the world was more colourful than post-soviet capitalism, and on the way passed by Judea, while searching for the legal implications of dreams. This turned out to be a problem for the trees in Tehran. Their roots were entangled in an antagonistic, hostile manner with those in Judea. After a course of negotiations on the international level, our plans to travel to the lands of Tehran entered a loop of uncertainty.

When we realized that the doors and borders were not wide open for our project to progress in the way it was conceived, we responded to the unfortunate new situation and proposed an alternative. Seeing living biota as having historical layers of knowledge and an ability to add new definitions to what it means to be human, we thought, maybe we could regard a tree as just a case that could be replaced with other living entities. Therefore, after a stormy night, we decided to shift our attention from the trees to the seas, and approach Iran without entering it, from the close proximity of its two northern neighbouring countries, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. These countries share the waters of the Caspian Sea with Iran, along with a complex ancient and more recent political and cultural history.

We then pursued our voyage in an attempt to take care of the wounds of the living sea-archive, or treating the Caspian Sea as a heritage site. We were told by a mythical bird called Simurgh that the Caspian is the only living archive of the Tethys Ocean, which existed 200 million years ago. Therefore, there is still an unresolved dispute among the gods regarding its categorization: is the Caspian a sea or a lake? It is salty like a sea and closed like a lake and, not surprisingly, this causes international conflicts – states surrounding it dispute the rights of exploitation as there are different laws for seas and for lakes. Nevertheless, we wanted to bathe in the Caspian waters, which is one of the most polluted areas in the world and, due to the oil industry, a place of species mass extinction. We considered the various ways that would allow us to construct boats and wings to travel over and underneath it: ecology, mythology, archaeology, geology, industry, cultural memory, political history and our personhood.

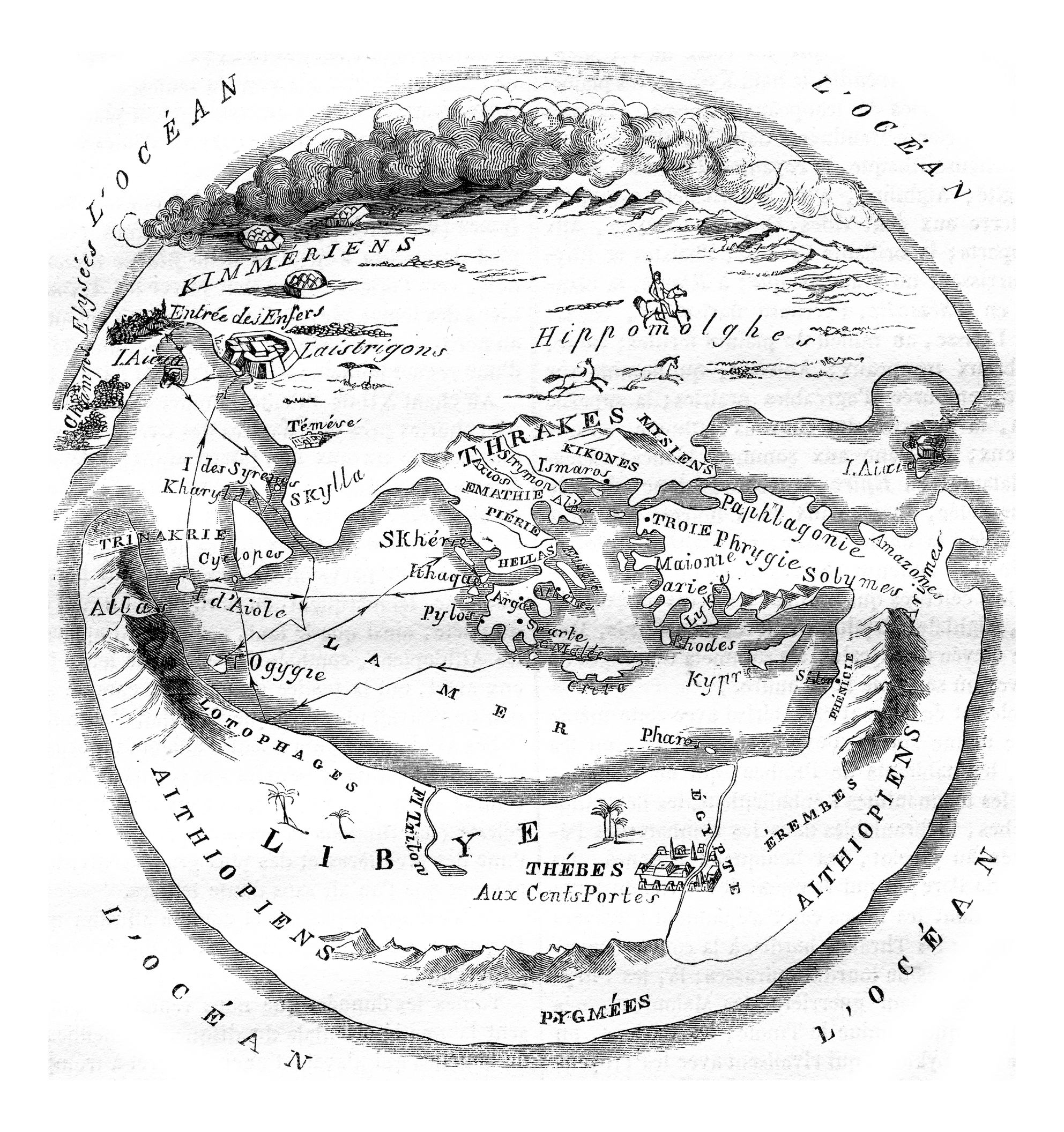

This looked indeed like an exciting travel plan. Not merely for the unbridgeable geographies that were ahead of us but also for the endless adventures, both embodied and imaginary, that were waiting for us in the depths of the sea storms. We remembered our great-grandfather Odysseus telling us: we spent nine days upon the sea, but on the tenth day we reached the land of the Lotus-eaters, who live on a food that comes from a kind of flower. When we had eaten and drunk I sent three of my company to see what manner of men the people of the place might be. They started at once, and went about among the Lotus-eaters, who did them no harm, but gave them to eat of the lotus, which was so delicious that those who ate of it left off caring about home, and did not even want to go back. Nevertheless, though they wept bitterly I forced them back to the ships and made them fast under the benches.

This looked indeed like an exciting travel plan. Not merely for the unbridgeable geographies that were ahead of us but also for the endless adventures, both embodied and imaginary, that were waiting for us in the depths of the sea storms. We remembered our great-grandfather Odysseus telling us: we spent nine days upon the sea, but on the tenth day we reached the land of the Lotus-eaters, who live on a food that comes from a kind of flower. When we had eaten and drunk I sent three of my company to see what manner of men the people of the place might be. They started at once, and went about among the Lotus-eaters, who did them no harm, but gave them to eat of the lotus, which was so delicious that those who ate of it left off caring about home, and did not even want to go back. Nevertheless, though they wept bitterly I forced them back to the ships and made them fast under the benches.

It is to this day unknown of what exact species the Lotus tree was, yet there are several candidates – one of them is Diospyros lotus, also known as the Date-Plum or Caucasian Persimmon. During Yalda Night, a festival where we celebrate the longest, deepest and darkest night of the year in Iran, Lotus fruit is one of the central elements consumed along with watermelon and pomegranate. Might it be, some of us wondered, due to its narcotizing effect, documented by Odysseus, that the night is old?

However adventurous our Caspian trip would have been, we all know what had happened instead. When the years had reached the magical number of two thousand and twenty, there made its appearance that deadly pestilence, which, whether disseminated by the influence of the celestial bodies, or sent upon us mortals by God in His just wrath by way of retribution for our iniquities, had had its origin some time before in the East, whence, after destroying an innumerable multitude of living beings, it had propagated itself without respite from place to place, and so, calamitously, had spread into the West. Despite all that human wisdom and forethought could devise to avert it, the doleful effects of the pestilence began to be horribly apparent by symptoms that showed as if miraculous. This made us remember our uncle, Giovanni Boccaccio, who wrote to us about the plague that devastated Europe around the 14th century.

The contemporary virulence pestilence closed borders for everyone, not only for those who bathed in enemy waters. The immersive, ethnographic, adventurous, travel-based project went virtual. This was shocking to all of us despite our different roles and grades of involvement. It created many moments, even days and weeks, of cry and crisis. Something that had started in love resulted in end-of-love conversations. However, we remained there, where the boat had left us – on a deserted island, looking for shelter and marvelling at what we had never seen before. Yet, at that devastating point, we received a letter from our beloved cousin Maurice Blanchot reminding us that ideas can arise only in the absence of physical reality, of the thing itself. In particular, writing becomes possible where words and thoughts take on a strange and mysterious reality of their own, and where, due to the lack, meaning and reference are allusive and ambiguous. And so we chose a rather speculative path filled with thorns.

Some of us started with reading second-grade scriptures about the adventurous travels of ancient Persian poets. But we also began talking among ourselves. We knew each other mostly by chance, through personal connections and through the time we shared bread in the past. Only one of us paid particular attention to botanical connections of the trees in Tehran. Only one of us had a photo camera. Only one of us knew of a machine that looped sounds. The others used memory, imagination and tools that worked with digits and speculation. We shared stories that we could tell about trees and stories that trees could tell about us. Soon we remembered that some trees, such as Weeping Willow, used their branches to pierce through our balconies when we were little and scare us at night with the shadows of black monsters. We remembered the reverberation of a shapeless monster that was looped through the rhythms of earth and wind as we watched it from the bed. This was particularly likely to happen if one lived on the outskirts of the city – facing Tochal mountain or living close to the water sources. Willow trees prefer growing near streams and rivers, where their roots are able to absorb underground reservoirs. The mature Weeping Willow has a unique shape. Its drooping branches are the reason why poetry and love coexist in Iran, where they call it the insane calix. A process that makes use of this tree’s abilities and which is at the centre of attention of environmental scientists is phytoremediation, or the use of plants to remove contamination from the soil and water near their roots. And its branches are also among its qualities, helping to turn ordinary people into flying Tarzans. Another beneficial ability is the production of salicylic acid – the same acid that is the main component of aspirin. Therefore, a tea made of willow leaves helps against headaches and fevers – we used it to reduce the pain caused by the new virus that roamed the world.

Some of us started with reading second-grade scriptures about the adventurous travels of ancient Persian poets. But we also began talking among ourselves. We knew each other mostly by chance, through personal connections and through the time we shared bread in the past. Only one of us paid particular attention to botanical connections of the trees in Tehran. Only one of us had a photo camera. Only one of us knew of a machine that looped sounds. The others used memory, imagination and tools that worked with digits and speculation. We shared stories that we could tell about trees and stories that trees could tell about us. Soon we remembered that some trees, such as Weeping Willow, used their branches to pierce through our balconies when we were little and scare us at night with the shadows of black monsters. We remembered the reverberation of a shapeless monster that was looped through the rhythms of earth and wind as we watched it from the bed. This was particularly likely to happen if one lived on the outskirts of the city – facing Tochal mountain or living close to the water sources. Willow trees prefer growing near streams and rivers, where their roots are able to absorb underground reservoirs. The mature Weeping Willow has a unique shape. Its drooping branches are the reason why poetry and love coexist in Iran, where they call it the insane calix. A process that makes use of this tree’s abilities and which is at the centre of attention of environmental scientists is phytoremediation, or the use of plants to remove contamination from the soil and water near their roots. And its branches are also among its qualities, helping to turn ordinary people into flying Tarzans. Another beneficial ability is the production of salicylic acid – the same acid that is the main component of aspirin. Therefore, a tea made of willow leaves helps against headaches and fevers – we used it to reduce the pain caused by the new virus that roamed the world.

That night we could hear the seismic rumbling of the earth in Tehran. The ground suddenly felt like never before. An earthquake makes one so violently aware of the unknown depths that one stands on. The Willow in the Ameneh nursery yard was weeping louder than ever, and the owls from Tochal changed their voices. Tree songs reminded us of the archangel Israfil when he is blowing his horn to announce the end of the world – an eschatological tradition according to which the sound of Israfil’s horn will be the final event of history.

Our relationship with trees grew even more complex. Their leaves were our food but some of them tasted of dead bitterness. Oak trees produce toxic tannins in their bark and leaves which could kill us while chewing on them. Still, many of us observed that trees are usually inhabited by diverse species. But not everyone knew that they are also inhabited by strange creatures in between animals and plants, which we were told are called fungi. Their appearance is of an alien planet, unearthly roots in a place with their spores dispersed by the wind. But their insides are made of chitin – a substance found in insects but not in plants. Just like birds, fungi do not photosynthesize, therefore they cannot produce food alone as oaks do. It might have been obvious to the fungi, but some of us realized only then that all animals depend on a form of mutual digestion.

Our relationship with trees grew even more complex. Their leaves were our food but some of them tasted of dead bitterness. Oak trees produce toxic tannins in their bark and leaves which could kill us while chewing on them. Still, many of us observed that trees are usually inhabited by diverse species. But not everyone knew that they are also inhabited by strange creatures in between animals and plants, which we were told are called fungi. Their appearance is of an alien planet, unearthly roots in a place with their spores dispersed by the wind. But their insides are made of chitin – a substance found in insects but not in plants. Just like birds, fungi do not photosynthesize, therefore they cannot produce food alone as oaks do. It might have been obvious to the fungi, but some of us realized only then that all animals depend on a form of mutual digestion.

However, we discovered that if a tree had a tongue with which to use grammar, the fungus would be the syntax. Let us say we have a tree in the right mood: the fungus enters inside its roots, penetrates it from within and feeds there. On the other hand, the fungus also provides medical services for the tree – it filters heavy metals which are more harmful to the tree’s roots than to the mushroom. Over the years, a web of underground fungi-root assemblage grows. It is called mycelium and, with its help, a tree-fungus body extends its reach and connects to the other mycelia. The mycelium is the network where the exchange of vital nutrients and viral information happens. In particular the Oak has an impressive root system, which mirrors its branches. Its roots have an ecological effect in reducing soil erosion. The Oak itself is a firm and resilient tree, which can withstand tough times, and is respected as the strongest tree in the woods. “May you be solid as flint, strong as oak and hardy as steel” – we would say when greeted in Lithuania during hard times.

Indeed, we soon realized that the ancient blessing, caught in the hair of a willow tree, is not far removed from the mesh of mycelium. The mesh lives and thinks, senses and experiences, interprets and represents, remembers and anticipates. Did we hear ants making jokes, feel bacterial despair and digest minerals with our roots? The mesh is the result of a cumulative past and, simultaneously, a predictive future. Trees need to be in society, speaking in the language of digestion, smell and taste. Alone a tree is at the mercy of wind and weather; they need us just as we need them to survive the un-meshing of urban developments, pollution and political crises.

After listening to a long tonal flip called the Iran-Iraq war, we followed the so-called renovation era in Iran, which caused millions of trees to become urban decoration. Before that, we recalled the plants that had an emergent and wild quality growing alongside the planned green urban spaces. The abundance of Wild Jasmines in Tehran, growing around fences, thriving in a haphazard manner, were not considered invasive weeds. They used to proudly nourish the herbal medication and perfume industry, and provide magic Persian flutes with wood tissue. After the renovation era, most of the Jasmines became a target for eradication. We wondered, shall we keep the corpses of dead trees to remind us of a city that we hardly recognize anymore?

After listening to a long tonal flip called the Iran-Iraq war, we followed the so-called renovation era in Iran, which caused millions of trees to become urban decoration. Before that, we recalled the plants that had an emergent and wild quality growing alongside the planned green urban spaces. The abundance of Wild Jasmines in Tehran, growing around fences, thriving in a haphazard manner, were not considered invasive weeds. They used to proudly nourish the herbal medication and perfume industry, and provide magic Persian flutes with wood tissue. After the renovation era, most of the Jasmines became a target for eradication. We wondered, shall we keep the corpses of dead trees to remind us of a city that we hardly recognize anymore?

There is this Neighbourhood in Tehran, too dense to walk through. It is called Amir Abad; we lived there. There are trees that grow in the perfect shape of a ball. We used to play with them, rolling them around on the ground. We used to explore a deadly dark pit with the help of anxious alien biotic creatures who spend just a few moments on earth before exploding into full-grown plants and filling the whole space in spring. There are pomegranate trees with branches that flirt with the air itself, and fruits larger than our heads, which we used to dissect meticulously in their different stages of growth, competing with ravens, who ate most of them. Our great grandmother, who had branches growing in all the corners of the house, did not know nostalgia. She and her pomegranates – only together could they moderate an ecosystem that regulated the ebb and flow of disparity and entropy of life, one that could store a great deal of juice, narratives, history of flirtatious branches, humidity, and only in each other’s embrace were they allowed to feel extremely old.

There is this Neighbourhood in Tehran, too dense to walk through. It is called Amir Abad; we lived there. There are trees that grow in the perfect shape of a ball. We used to play with them, rolling them around on the ground. We used to explore a deadly dark pit with the help of anxious alien biotic creatures who spend just a few moments on earth before exploding into full-grown plants and filling the whole space in spring. There are pomegranate trees with branches that flirt with the air itself, and fruits larger than our heads, which we used to dissect meticulously in their different stages of growth, competing with ravens, who ate most of them. Our great grandmother, who had branches growing in all the corners of the house, did not know nostalgia. She and her pomegranates – only together could they moderate an ecosystem that regulated the ebb and flow of disparity and entropy of life, one that could store a great deal of juice, narratives, history of flirtatious branches, humidity, and only in each other’s embrace were they allowed to feel extremely old.

They were much older than us, much older than our grandmothers. Some trees have not only seen revolution but also witnessed Iranianness itself. A pine can live for 5000 years. The oldest tree on earth is more than 9500 years old and stands in what is now Sweden. When we visited it, it did not look old at all. In Iran, we know the Cupressaceae family as one of the ancients. We considered Cypresses precious because of their close relationship to the saints throughout history: the Cypress of Abarkuh, between 4000 and 5000 years old, was planted by the Prophet Zoroaster himself. There was another – the Cypress of Kashmar, which, we were told, Zoroaster had planted from a branch that he had brought from heaven. Cypresses have been cherished in our parents’ gardens and praised in their poems. Telling legends and practicing mythology around certain trees is a protective tactic perhaps, woven in with the threads of loss and rebirth as we become particularly sensitive to the environmental impacts and interventions that are hard for those of us who are slow and aged.

They were much older than us, much older than our grandmothers. Some trees have not only seen revolution but also witnessed Iranianness itself. A pine can live for 5000 years. The oldest tree on earth is more than 9500 years old and stands in what is now Sweden. When we visited it, it did not look old at all. In Iran, we know the Cupressaceae family as one of the ancients. We considered Cypresses precious because of their close relationship to the saints throughout history: the Cypress of Abarkuh, between 4000 and 5000 years old, was planted by the Prophet Zoroaster himself. There was another – the Cypress of Kashmar, which, we were told, Zoroaster had planted from a branch that he had brought from heaven. Cypresses have been cherished in our parents’ gardens and praised in their poems. Telling legends and practicing mythology around certain trees is a protective tactic perhaps, woven in with the threads of loss and rebirth as we become particularly sensitive to the environmental impacts and interventions that are hard for those of us who are slow and aged.

On average, most trees live not thousands but a couple of hundreds of years. This is due to slow growth – the faster they grow, the younger they die. We heard a rumour that presently trees around the world are growing faster than ever. Warmer temperatures and rising atmospheric carbon dioxide are driving the accelerated growth. City trees in particular suffer more from fast-growth than their rural relatives. And city trees die younger. For each season a tree survives, it adds a ring around the outer layer of its trunk. Each ring reports of a plentiful or deprived season: years with enough rain lead to thicker rings whereas dry, stressful times leave narrow rings. It is the tree stems that allowed us to track the writings of the climate.

We could see, as though through a camera lens, how the city became fragmented into tiny landscapes that did not fit the frame. It reminded the older among us of the ancient Plane trees living squeezed in concrete in the area of Gheytarieh. Trees are good at not only adapting to a space but also squeezing in the corners of semiotic representations. Sometimes cherished and sometimes vilified, trees always tend to mean something. Not that the tree should care about it, but let us say Cercis siliquastrum, or Judas tree, earned its common name from a legend. It is said that Judas Iscariot, the betrayer of Christ, hanged himself from a tree, after which its white flowers turned red from blood and shame. This must have been a jealous ecosystem that made his name infamous. Most likely, the name Judas tree is a corrupted derivation from the French common name Arbre de Judée meaning tree of Judea, referring to the ancient name of a region in the Palestine of today, where the tree is typically seen growing on the hills. In Tehran, on Felestin street we could smell its gorgeous pink blossoms radiating a hypnotizingly sweet scent.

We could see, as though through a camera lens, how the city became fragmented into tiny landscapes that did not fit the frame. It reminded the older among us of the ancient Plane trees living squeezed in concrete in the area of Gheytarieh. Trees are good at not only adapting to a space but also squeezing in the corners of semiotic representations. Sometimes cherished and sometimes vilified, trees always tend to mean something. Not that the tree should care about it, but let us say Cercis siliquastrum, or Judas tree, earned its common name from a legend. It is said that Judas Iscariot, the betrayer of Christ, hanged himself from a tree, after which its white flowers turned red from blood and shame. This must have been a jealous ecosystem that made his name infamous. Most likely, the name Judas tree is a corrupted derivation from the French common name Arbre de Judée meaning tree of Judea, referring to the ancient name of a region in the Palestine of today, where the tree is typically seen growing on the hills. In Tehran, on Felestin street we could smell its gorgeous pink blossoms radiating a hypnotizingly sweet scent.

By now you already know that we made weird long-distance calls, turning them into inspiration and food for computer animation. To create our sounds we performed along with a sampler and sequencer, which contained eight separate sample machines, each connected to the sixty-four steps of a sequencer. We made them loop and made arrangements of loops of the sounds, knowledge, memories, perceptions, body parts, minerals and ideas. We stayed within the imagination, digital apparatus, telecommunication, human narrative, and mediated exchange of verbalized memories. A definition of Tehran’s lifeworld did remain an open project.

By now you already know that we made weird long-distance calls, turning them into inspiration and food for computer animation. To create our sounds we performed along with a sampler and sequencer, which contained eight separate sample machines, each connected to the sixty-four steps of a sequencer. We made them loop and made arrangements of loops of the sounds, knowledge, memories, perceptions, body parts, minerals and ideas. We stayed within the imagination, digital apparatus, telecommunication, human narrative, and mediated exchange of verbalized memories. A definition of Tehran’s lifeworld did remain an open project.